I should pause for a moment since I am stepping in hot water by the very mention of “postmodern,” a term that was the dominant topic of academic debate for almost a generation but is now regarded as a fad or trend that was useful only in making careers. On the whole, I agree with this view. The postmodern fixation seemed to help demolish Marxism, and to replace leftist radicalism with subjectivism, apocalypticism, and a regressive “retro” outlook within mass culture. I would recommend to the reader Andrew Britton’s essay on postmodernism, a withering, closely-argued comment on the impoverished state of academe during the Reagan-Thatcher era and the utility of postmodernism in supporting that climate of reaction (Britton 2008).[i] His words, never properly answered (although he found, after his death, good company among Christopher Norris and others), have relevance to the current moment.

While I agree that much of the “theory” generated by postmodernism (especially Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard and their ilk) is mostly worthless, reactionary hogwash, it seems reasonable to say that certain features of the current capitalist state make our situation one that might reasonably be labeled postmodern. Some of the aspects of this state include the prevailing idea that the subversive aspects of modernism, along with most notions of the progressive advancement of humanity, are simply finished, along with the “grand narrative” of Marxism, viewed as hopelessly naïve and outdated; the near-triumph of the corporate mass media in shaping consciousness, and the attendant assault on class consciousness; the rise of the cybernetic revolution and the “information age,” which, while showing possibilities of a politically revolutionary nature, also suggests a new and alarming climate of alienation; the deindustrialization of large sectors of the globe, especially the U.S., bringing the preeminence of speculation and finance capital and the demise of “entrepreneurship,” especially as retail business is consolidated through the Internet and the various conglomerates functioning within it; the movement of imperialism into cybernetic and media-dependent representation, so that imperial conquest is abstracted to prevent meaningful outrage and resistance; the demise of humanist representational art (the bourgeois artists accepting the notion of the human being as worthless to capital), and art that offers an adversarial perspective toward late capitalism (while some venues, like the Whitney Museum in New York, or the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), feature numerous postindustrial “installations” that at times point to the continued exploitation and bloodletting under capital, they very often partake of an aestheticized wallowing in decay, a “grooving” on images of social and industrial breakdown that the bourgeoisie patronizing such shows itself created).

While I agree that much of the “theory” generated by postmodernism (especially Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard and their ilk) is mostly worthless, reactionary hogwash, it seems reasonable to say that certain features of the current capitalist state make our situation one that might reasonably be labeled postmodern. Some of the aspects of this state include the prevailing idea that the subversive aspects of modernism, along with most notions of the progressive advancement of humanity, are simply finished, along with the “grand narrative” of Marxism, viewed as hopelessly naïve and outdated; the near-triumph of the corporate mass media in shaping consciousness, and the attendant assault on class consciousness; the rise of the cybernetic revolution and the “information age,” which, while showing possibilities of a politically revolutionary nature, also suggests a new and alarming climate of alienation; the deindustrialization of large sectors of the globe, especially the U.S., bringing the preeminence of speculation and finance capital and the demise of “entrepreneurship,” especially as retail business is consolidated through the Internet and the various conglomerates functioning within it; the movement of imperialism into cybernetic and media-dependent representation, so that imperial conquest is abstracted to prevent meaningful outrage and resistance; the demise of humanist representational art (the bourgeois artists accepting the notion of the human being as worthless to capital), and art that offers an adversarial perspective toward late capitalism (while some venues, like the Whitney Museum in New York, or the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), feature numerous postindustrial “installations” that at times point to the continued exploitation and bloodletting under capital, they very often partake of an aestheticized wallowing in decay, a “grooving” on images of social and industrial breakdown that the bourgeoisie patronizing such shows itself created).To my mind, postmodern cinema rarely offers challenges to the contemporary crisis. At its worst, it reinforces it by snide gloating at dumb schmucks (I think Todd Solondz may be representative, but it would be ungenerous not to acknowledge his comedy as effective, caustic satire), by above-it-all, obscure hipsterism (the Wes Andersons), by collages of films from the recent past that show outright disrespect for these films as well as the audience (Tarantino), and the various oddities of David Lynch, who, after promising beginnings, moved from underside-of- suburbia “quirkiness” fully demonizing the Other (Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks) into obscurantism that seems focused on Lynch’s fear of the schoolyard bully, usually constructed as a malevolent queer (Lost Highway, et al.).

I am not suggesting that Drive responds to each and every aspect of the postmodern climate I have (tentatively) outlined, but I think that it, like all postmodern films that I recall, fails to be revolutionary in the slightest. It strikes me that the most valuable works of postmodern art (and I think Drive may be one) offer a probing look, a sort of diagnosis, of the conditions around us and their affect on humanity. I have argued that Brokeback Mountain is remarkable not only for its valiant comment on the gay man as Other, but for its demolition of the masculine ideal established by bourgeois patriarchal capitalist art and once-preeminent, defining genres like the Western, especially the “strong, silent” image of the male essential to the Hollywood cinema (Sharrett 2009). This thoughtful undermining of the conventions of mainstream cinema is one of the healthy, adversarial aspects of the current climate, its impulses by no means a response simply to the situation of postmodernity. Michael Mann has never reached this level of achievement, but his image of the decline of the male professional and the male group is compelling, as is his focus on the strong homoerotic current underneath the representation of the male group from the old Hollywood (Rio Bravo is most crucial for its largely unconscious and therefore repressed gay impulse within male group representation) to the present (the male pieta at the end of Heat). Drive expands on several of Mann’s themes, particularly the ultimate ineffectuality of the male-as-professional, and utter isolation of the contemporary human subject within the corporatized cityscape.[ii]

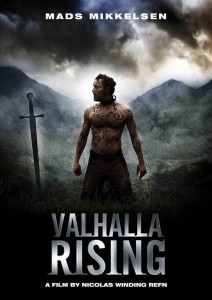

The obvious objection to a serious consideration of Drive, certainly for anyone familiar with his work, is that Refn appears to be “selling out,” making a Hollywood film with a cast of rising stars, using a plot that is shopworn, and playing into the “hot car” fad. I was prepared with a sell-out charge with the release of Valhalla Rising (2009), which I thought would be another CGI-driven sword-and-sandal epic, but this film’s eccentricity, its austere, almost minimalist image of the barbarism of the Crusades and the “founding” of the New World places barbarism firmly at the feet of Christianity, although the film veers very close to nihilism, and the rhapsodical indulgence of Malick , but with a much darker hue. But it seems to me a strikingly radical film: the Dark Ages are not “saved” by Christianity, but further darkened by it.

The obvious objection to a serious consideration of Drive, certainly for anyone familiar with his work, is that Refn appears to be “selling out,” making a Hollywood film with a cast of rising stars, using a plot that is shopworn, and playing into the “hot car” fad. I was prepared with a sell-out charge with the release of Valhalla Rising (2009), which I thought would be another CGI-driven sword-and-sandal epic, but this film’s eccentricity, its austere, almost minimalist image of the barbarism of the Crusades and the “founding” of the New World places barbarism firmly at the feet of Christianity, although the film veers very close to nihilism, and the rhapsodical indulgence of Malick , but with a much darker hue. But it seems to me a strikingly radical film: the Dark Ages are not “saved” by Christianity, but further darkened by it. It is obviously the case that Refn is now working on a larger scale than in his early films in Denmark (meaning a bit more money—the film itself is modest, focused, and restrained, except for the violence), but Drive picks up the exploration he undertook with his remarkable Pusher films, Bleeder (1999), and the interesting if off-putting Bronson (2008), damaged by an ill-conceived fusion of Brecht and music hall burlesque, Refn’s “distanciation” approach in essaying the utter failure of the criminal justice system, with it mistreatment of England’s “most dangerous men.” Bleeder is a stunning work in its response to films such as Clerks (1994), which posits underemployed, bored young men as simply bored and ridiculous, while Refn’s film shows the current of racism, misogyny, and deadly violence that runs through their frustration. The extraordinary Pusher II: With Blood on My Hands (2004) is one of the most underrated films of recent years, important for its close association of crime with the working class, not in order to demonize this class, but to convey a sense of the impossibility of working class survival under the present phase of capitalism without resorting to crime. This social critique is closely tied to the Oedipal construct, and the demands of the monstrous father. Refn remarks in his DVD commentary that he wanted the film to be accessible as a melodrama, readable to anyone not so much as a crime film but as a comment on family dynamics. Tonny, portrayed by the formidable Mads Mikkelsen, a Refn regular, is an ex-convict who returns to work for his father (called the Duke, which according to Refn was a stab at the ultimate primal father, John Wayne). The Duke runs a car theft operation, into which Tonny uneasily integrates. What is most enthralling about Mikkelsen’s performance is his sense of emotional frailty and diffidence, despite his tattoos and attempts at a threatening outward demeanor (the actor’s range is remarkable for those of us who became familiar with him through his role as Le Chiffre in Casino Royale—it is a pity he failed to castrate James Bond). It is clear that Tonny has a very damaged sense of self. His murder of his father is based less on failed criminal operations than on the father’s constant berating of his son, his bullying him into becoming a “real man.” Pusher II underscores a key concern of Refn: the male as acted upon, and the impossibility of men and women thriving under current social-economic assumptions.

It is obviously the case that Refn is now working on a larger scale than in his early films in Denmark (meaning a bit more money—the film itself is modest, focused, and restrained, except for the violence), but Drive picks up the exploration he undertook with his remarkable Pusher films, Bleeder (1999), and the interesting if off-putting Bronson (2008), damaged by an ill-conceived fusion of Brecht and music hall burlesque, Refn’s “distanciation” approach in essaying the utter failure of the criminal justice system, with it mistreatment of England’s “most dangerous men.” Bleeder is a stunning work in its response to films such as Clerks (1994), which posits underemployed, bored young men as simply bored and ridiculous, while Refn’s film shows the current of racism, misogyny, and deadly violence that runs through their frustration. The extraordinary Pusher II: With Blood on My Hands (2004) is one of the most underrated films of recent years, important for its close association of crime with the working class, not in order to demonize this class, but to convey a sense of the impossibility of working class survival under the present phase of capitalism without resorting to crime. This social critique is closely tied to the Oedipal construct, and the demands of the monstrous father. Refn remarks in his DVD commentary that he wanted the film to be accessible as a melodrama, readable to anyone not so much as a crime film but as a comment on family dynamics. Tonny, portrayed by the formidable Mads Mikkelsen, a Refn regular, is an ex-convict who returns to work for his father (called the Duke, which according to Refn was a stab at the ultimate primal father, John Wayne). The Duke runs a car theft operation, into which Tonny uneasily integrates. What is most enthralling about Mikkelsen’s performance is his sense of emotional frailty and diffidence, despite his tattoos and attempts at a threatening outward demeanor (the actor’s range is remarkable for those of us who became familiar with him through his role as Le Chiffre in Casino Royale—it is a pity he failed to castrate James Bond). It is clear that Tonny has a very damaged sense of self. His murder of his father is based less on failed criminal operations than on the father’s constant berating of his son, his bullying him into becoming a “real man.” Pusher II underscores a key concern of Refn: the male as acted upon, and the impossibility of men and women thriving under current social-economic assumptions.There have been some real missteps. Refn’s Fear X (2005) contains a momentary meditation on marriage as a trap, with the obsessive husband (Jon Turturro, whose very casting suggests he must be the killer) a possible wife-murderer, but the film drowns in its Lynchian atmospherics, and a failure to write a more thoughtful script, caving in instead to “Kafkaesque” feelings of persecution and unknowability.

The fragile sense of the male self, complementing the hero’s monstrousness, is basic to Drive. A young man (Ryan Gosling) referred to in the film only as “Kid” (he is listed in the credits as Driver), supplements his income as a mechanic and Hollywood stunt driver by being the wheel man in hold-ups (holding “extra jobs” to get by, leading one to criminality, extends ideas of the Pusher films about the dreadful state of the working class). He has an employer/mentor named Shannon (Bryan Cranston) who runs a garage where the two men fix cars. The film quickly undermines the older man/young acolyte idea so basic to Westerns, challenged in films like Se7en (1995). Shannon is a damaged, weary man of poor judgment who has nothing to teach; the Kid seems smarter and more confident than his boss. Shannon isn’t really a mentor to the Kid in the sense that he groomed him; the Kid appeared at the garage out of nowhere.

The fragile sense of the male self, complementing the hero’s monstrousness, is basic to Drive. A young man (Ryan Gosling) referred to in the film only as “Kid” (he is listed in the credits as Driver), supplements his income as a mechanic and Hollywood stunt driver by being the wheel man in hold-ups (holding “extra jobs” to get by, leading one to criminality, extends ideas of the Pusher films about the dreadful state of the working class). He has an employer/mentor named Shannon (Bryan Cranston) who runs a garage where the two men fix cars. The film quickly undermines the older man/young acolyte idea so basic to Westerns, challenged in films like Se7en (1995). Shannon is a damaged, weary man of poor judgment who has nothing to teach; the Kid seems smarter and more confident than his boss. Shannon isn’t really a mentor to the Kid in the sense that he groomed him; the Kid appeared at the garage out of nowhere.Anxious for money to bankroll the Kid as a major stock car driver, Shannon solicits an old associate, a gangster named Bernie Rose (comedian Albert Brooks in the best role of his career). The Kid forms a relationship with Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her young son Benicio (Kaden Leos), for whom he has charming affinity. Irene is awaiting the release from prison of her husband Standard (Oscar Isaac). Despite his relationship with Irene, Standard, after a slightly testy first meeting, holds no ill will toward the Kid, who is integrated into the family. When Standard is savagely beaten by hoodlums who want payback for his jailhouse protection, the Kid comes to his aid, going so far as to be the driver in a pawn shop robbery designed to pay off Standard’s debts, but which goes terribly awry and brings to the forefront Bernie Rose and his mob partner Nino (Ron Perlman).

More than the work of Michael Mann and some postmodern graphic artists, the most obvious point of reference is George Stevens’s Shane (1952), a film cited endlessly in popular cinema of the 80s when Joseph Campbell and his “hero’s journey” charlatanism were in vogue (Star Wars, Mad Max 2, Pale Rider, etc.). Refn makes perhaps the most thoughtful use of Shane yet. He examines the centrality of its conventions, its utopian notions of the community and the male hero. The Kid is a Stranger from Nowhere, the figure who traditionally enters a community in order to show it its potentials, sacrificing himself in the process. He integrates well within a Little Family, becoming a friend to the father even as sexual attraction continues between the Stranger and the wife (underplayed in Shane, explicit in Drive, although there is notably no sex scene between the Kid and Irene).

While the father is at first threatened by the Stranger (Joe Starrett is ready to shoot Shane; Standard seems at a bit perturbed at his first encounter with the Kid), he recognizes that he is in need of the Stranger’s powers, particularly as a protector of his family. But the fathers are unattractive men also attracted to the Stranger’s sexual charisma, suggesting the gay impulse as well as the father’s castration by domesticity, something the wandering Stranger has escaped. The Stranger signifies improved conditions for the Little Family, which lives in poverty. In Shane, Marion brings out her best dinnerware to host Shane. In Drive, Irene and Standard host the Kid at a table set with dime store glassware—the Kid will end up destroying the family instead of helping it prosper. The little boy, in Drive as in Shane, takes an immediate liking to the Stranger, and the Stranger for the child, whose protection becomes a priority. The boy is a potential hero, another masculine ideal to replace the Stranger, a figure of unfettered masculinity more potent than the biological father. The child’s love of the Stranger becomes his benediction, a sense that he, at one level, possesses, like the land, complete benevolence and innocence. But in Drive, Benicio’s affection for the Kid merely shows how a child’s judgment can be wrong. There is no running after the Kid at the end of Drive.

Like the archetypal Strangers such as Shane, the Kid has his own iconographic coding. Shane is garbed in buckskin (the triumph over Nature), with a silver and black gunbelt (the malevolence of Culture). The Kid wears a quilted white windbreaker with a gold and red scorpion embroidered on its back. At times, like the opening scene, the jacket is lit to seem nearly black. Any cineaste will associate the jacket’s emblem with Scorpio Rising (1964), Kenneth Anger’s canny demolition of the male group as a hideout for gay impulses, or perhaps the opening of Bunuel/Dali’s L’Age d’Or, with the scorpion associated with sex, excrement, and death (as Martin Short notes), suggesting the insistence within male culture of conflating anality and homosexuality with contamination and death (long before the AIDS era).[iii] If I may drop in some anthropological theory, like Shane’s black gunbelt, the Kid’s scorpion can be read as a sign of homeopathic magic, a dose of which will save the community, after which the shaman-hero must be banished. But in the instance of the Kid, this magic seems almost wholly negative. His prowess is evident, but his energies manifest a disturbance, to the point that he seems insane, his backstory less intriguing than unnerving as one imagines it. It might be argued that Drive can be usefully compared to Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), another work sometimes seen as a reworking of Shane. But in Teorema the Stranger is revolutionary; he destroys the bourgeois family and all of the assumptions of the capitalist state upon which it rests. In Drive, the Kid is almost purely destructive despite his apparent good intentions, the suggestion being that there is no place to go, no possibility of a new world once the old one is destroyed.

Like the archetypal Strangers such as Shane, the Kid has his own iconographic coding. Shane is garbed in buckskin (the triumph over Nature), with a silver and black gunbelt (the malevolence of Culture). The Kid wears a quilted white windbreaker with a gold and red scorpion embroidered on its back. At times, like the opening scene, the jacket is lit to seem nearly black. Any cineaste will associate the jacket’s emblem with Scorpio Rising (1964), Kenneth Anger’s canny demolition of the male group as a hideout for gay impulses, or perhaps the opening of Bunuel/Dali’s L’Age d’Or, with the scorpion associated with sex, excrement, and death (as Martin Short notes), suggesting the insistence within male culture of conflating anality and homosexuality with contamination and death (long before the AIDS era).[iii] If I may drop in some anthropological theory, like Shane’s black gunbelt, the Kid’s scorpion can be read as a sign of homeopathic magic, a dose of which will save the community, after which the shaman-hero must be banished. But in the instance of the Kid, this magic seems almost wholly negative. His prowess is evident, but his energies manifest a disturbance, to the point that he seems insane, his backstory less intriguing than unnerving as one imagines it. It might be argued that Drive can be usefully compared to Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), another work sometimes seen as a reworking of Shane. But in Teorema the Stranger is revolutionary; he destroys the bourgeois family and all of the assumptions of the capitalist state upon which it rests. In Drive, the Kid is almost purely destructive despite his apparent good intentions, the suggestion being that there is no place to go, no possibility of a new world once the old one is destroyed.The Kid

Ryan Gosling’s rendering of the strong, silent type is remarkable for its contradictions. The few words he more or less mumbles are in keeping with the manifestation of this character in the Western, but here the persona can be understood as simply illiterate, a victim of the failures of the educational system. At times his voice is barely audible. He speaks with a monotone, but at one moment seems breathless and nervous (his phone call to Nino from the strip joint). In his final encounter with Irene, when he asks if he might look after her and her son, he is a downcast child, his eyes toward the floor. Irene slaps him. At best, the Kid may be a “man without qualities,” but unlike the cynics and moral cowards of some nineteenth-century novels, the Kid may have the kind of low affect signifying psychopathy, despite his gestures for the Little Family.

The notion of the Kid as monster is emphasized by his roiling rage. He is capable of standing with his arms folded, the image of self-possession and affability (his brief conversation with the badly injured Standard), but there is a sense of an undercurrent of anger that seems psychopathic and outweighs his generosity. We regularly see shots of his fist, gloved or ungloved, as the Kid flexes it; the audio track emphasizes the stretching leather and cracking knuckles. The menace of the image is clearer when the Kid holds an object, such as the hammer he uses to attack Cook in the strip joint. The Kid’s affability is completely erased in the final elevator scene, where the Kid kisses Irene goodbye in slow motion (one of several operatic longueurs in the film), then grabs a threatening hoodlum and stomps his skull to a pulp (the ridiculous scene, obviously derived from Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible, is not one of Refn’s best decisions—indeed, it is one of the moments that undermines Refn as a mature director). The Kid slowly straightens up and turns to face a shocked Irene, who sees the monstrousness of the man who fascinated her. The moment displays the death wish cancelling eros.

The notion of the Kid as monster is emphasized by his roiling rage. He is capable of standing with his arms folded, the image of self-possession and affability (his brief conversation with the badly injured Standard), but there is a sense of an undercurrent of anger that seems psychopathic and outweighs his generosity. We regularly see shots of his fist, gloved or ungloved, as the Kid flexes it; the audio track emphasizes the stretching leather and cracking knuckles. The menace of the image is clearer when the Kid holds an object, such as the hammer he uses to attack Cook in the strip joint. The Kid’s affability is completely erased in the final elevator scene, where the Kid kisses Irene goodbye in slow motion (one of several operatic longueurs in the film), then grabs a threatening hoodlum and stomps his skull to a pulp (the ridiculous scene, obviously derived from Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible, is not one of Refn’s best decisions—indeed, it is one of the moments that undermines Refn as a mature director). The Kid slowly straightens up and turns to face a shocked Irene, who sees the monstrousness of the man who fascinated her. The moment displays the death wish cancelling eros.The Kid as essentially a destroyer is evident throughout the film. He is conned into assisting in an absurd robbery that goes horribly wrong (so much for the hero’s sense of judgment). He tells the unreliable Shannon about the robbery, resulting in Shannon’s grisly death at the hands of Bernie Rose. The Kid goes on a pointless revenge spree, donning a latex mask used for his stunt scenes as he pursues pal Nino into the night. (The mask, which has vaguely discernable features, seems to emphasize the Kid as soulless, as essentially empty of personality). After crashing into his car, the Kid, looking like the hulking slashers from horror franchises, approaches Nino slowly, the gothic effect increasing, as he drowns Nino in the surf. (I should note that Nino, whose real name is Izzy, a Jew who wants to be a tough Italian Mafioso, is another of the film’s emblems of threatened masculinity—he uses the word “fuck” insistently to “toughen” his speech, a common enough speech device for men and boys, and complains to Bernie about the real gangsters who want to “pinch his cheeks.”)

But most unnerving of all is the Kid’s torment of the traitorous Blanche (Christina Hendricks) as they hide in a hotel room after the failed pawnshop robbery. The Kid slaps her and pins her to the bed, pointing an accusing gloved finger at her face. His voice is threatening chiefly in its foregrounding of the flat, monotone affect apparent throughout the film. The Kid’s torment of Blanche is followed by the assault on the motel room by two shotgun-wielding gangsters, one of whom blows Blanche’s head off. The Kid stabs him with a piece of metal from the window sash, then shoots the other gangster. Another longueur occurs, as the blood-covered face of the Kid moves slowly back and forth in the shadows, the scene accented by late afternoon sun. The film turns into perverse opera, as the Kid becomes a signifier of the world’s violence—he, as much as the gangsters, is responsible for the decapitation of Blanche, and every other disaster. The Kid’s appearances are linked to violence and death—Standard is beaten shortly after he meets the Kid; Shannon is murdered because of the Kid’s unwise use of him as confessor. Above all, the Kid accomplishes very little. At the end, Standard and Shannon are dead, along with the two key gangsters. Irene is alone with her son; Bernie’s promise to the Kid that Irene is “off the map” seems less than believable. Irene knocks forlornly at the door of the Kid’s empty apartment.

But most unnerving of all is the Kid’s torment of the traitorous Blanche (Christina Hendricks) as they hide in a hotel room after the failed pawnshop robbery. The Kid slaps her and pins her to the bed, pointing an accusing gloved finger at her face. His voice is threatening chiefly in its foregrounding of the flat, monotone affect apparent throughout the film. The Kid’s torment of Blanche is followed by the assault on the motel room by two shotgun-wielding gangsters, one of whom blows Blanche’s head off. The Kid stabs him with a piece of metal from the window sash, then shoots the other gangster. Another longueur occurs, as the blood-covered face of the Kid moves slowly back and forth in the shadows, the scene accented by late afternoon sun. The film turns into perverse opera, as the Kid becomes a signifier of the world’s violence—he, as much as the gangsters, is responsible for the decapitation of Blanche, and every other disaster. The Kid’s appearances are linked to violence and death—Standard is beaten shortly after he meets the Kid; Shannon is murdered because of the Kid’s unwise use of him as confessor. Above all, the Kid accomplishes very little. At the end, Standard and Shannon are dead, along with the two key gangsters. Irene is alone with her son; Bernie’s promise to the Kid that Irene is “off the map” seems less than believable. Irene knocks forlornly at the door of the Kid’s empty apartment.Landscape and Iconography

Car chases in films have long since became so tiresome that a common refrain when leaving a bad film was “at least there was no car chase,” so a film that seems centered on such, especially at a time when car smash-ups are de rigueur in movies, seem less than worthy of serious consideration. It is amazing, therefore, how Refn makes such superb use of the chase, and conjoins the automobile to his sense of Los Angeles. The Kid’s skill at the wheel is established in the opening heist, as he both powers his car down streets and coolly slides into cover when he sees danger. But his taut, expressionless face signifies the death wish as much as traditional machismo.

Forward motion is a dominant visual feature of the film, obviously when we look at the highway from the Kid’s point of view in his various souped-up cars. But this movement ultimately suggests a sense of turmoil and disarray as much as the Kid’s competence at the steering wheel. Behind the opening credits is the forward motion of a helicopter flyover of nighttime Los Angeles, with its overwhelming sprawl and electric lighting (we have in LA a key visual reminder of why the planet is burning up). Artificial light is simulated throughout the film, from Refn’s color palette to his credit design. Tracking shots are complemented by static images, in the film’s philosophical/political dynamic of live against death, eros versus the death wish. Before the flyover of the city, we see the Kid speaking quietly on the phone with a hoodlum wishing to employ his services—the sense of isolation is a visual trope to which I will return. There is a pair of tracking shots in a food market, using a lens that compresses space, as the Kid and Irene shop in opposite aisles. The Kid pauses for a moment to overhear Irene chatting with her young son, an adolescent approach to finding a way to win over Irene. The market scene, with the garish commodities “popping,” is one of the film’s moments of confinement, undercutting the “power of the open road” to which the Kid ostensibly has access.

A remarkable three-shot sequence immediately precedes Shannon’s first meeting with Bernie Rose. Irene is alone in her apartment after her first sexually-charged encounter with the Kid. The scene cuts to a tracking shot that closes in on a window overlooking a park and the sidewalk nearby. Several tall, arrow-straight palm trees form vertical lines in the image; the lines are replicated in the next shot, of the Kid leaning against a window, looking out, followed by a shot of the façade of Nino’s Pizzeria and the strip-mall stores immediately adjoining it. The steel frame of the store repeats the verticals, now complemented fully by horizontals. The idea of the city as prison comes through in this and other visual strategies, including images of lonely men in lonely rooms, images saturating film noir, smartly revamped by Michael Mann.

Refn’s innovation of the strategy mostly forces the viewer to contemplate the Kid’s psychology. He sits by himself in a dark room fixing a carburetor (the hero and his weapon), a table lamp the sole source of light. The Kid sits alone in a kitschy, orange-colored diner, framed by a large bay window, as he awaits Irene. He sits with his back to the camera in another shot, at the end of a long, mostly empty counter in a diner. A man enters the scene and approaches the Kid. The film cuts to a close low-angle shot of the Kid, who responds by telling the man to leave before he “kicks [his] teeth down his throat.” Based on the fragment of the man’s chatter, we can assume that the Kid was once betrayed by this man, but the moment, lacking real context, points to the Kid’s psychopathy. Frames-within-frames recur, such as the shot of Blanche seated at screen left, her image reflected in the motel mirror, or Irene facing us as she talks to the Kid, whose shadowed faced is reflected in a small mirror near her left shoulder. The technique, suggesting the “other side” of the Kid, refers as much to artists like Sirk and Antonioni as to the postmodernists in the use of surfaces to convey entrapment, the world as all surface, and the impossibility of making human contact.

Refn’s innovation of the strategy mostly forces the viewer to contemplate the Kid’s psychology. He sits by himself in a dark room fixing a carburetor (the hero and his weapon), a table lamp the sole source of light. The Kid sits alone in a kitschy, orange-colored diner, framed by a large bay window, as he awaits Irene. He sits with his back to the camera in another shot, at the end of a long, mostly empty counter in a diner. A man enters the scene and approaches the Kid. The film cuts to a close low-angle shot of the Kid, who responds by telling the man to leave before he “kicks [his] teeth down his throat.” Based on the fragment of the man’s chatter, we can assume that the Kid was once betrayed by this man, but the moment, lacking real context, points to the Kid’s psychopathy. Frames-within-frames recur, such as the shot of Blanche seated at screen left, her image reflected in the motel mirror, or Irene facing us as she talks to the Kid, whose shadowed faced is reflected in a small mirror near her left shoulder. The technique, suggesting the “other side” of the Kid, refers as much to artists like Sirk and Antonioni as to the postmodernists in the use of surfaces to convey entrapment, the world as all surface, and the impossibility of making human contact.The lonely men/lonely rooms visual pattern recalls the importance of specific graphic artists such as David Hockney, Eric Fischl, Ed Ruscha, Robert Longo, and especially Edward Hopper, whose overly-cited work has made the visual styles of many films noirs tiresome. But Hopper may have usefulness here. Hopper was a conservative who saw alienation simply as the way things are, and had no time for talk about other forms of society, so the temperament underlying his aesthetic seems relevant to contemporary culture, and Drive’s aesthetic and refusal of political commitment.

Refn tends to shoot in fairly close, capturing small vignettes of the city rather than cityscapes. Here the sources are as much photographers like William Eggleston and Stephen Shore as painters, the effect being to show instances of decay, such as unwholesome restaurants (the pizzeria with its strange red-and-white glass door that replicates its tablecloths), garages, diners, an image of a pawnshop on an antiquated TV set. When the Kid takes Irene and Benicio on a little excursion, one of the very few light moments, he drives them down the concrete surface of the Los Angeles River, a much-used movie location. This “river,” with its absolute human artifice—it is mostly a human construction—has only a stream of (filthy?) water in its center. The trio disembarks at a swatch of nature (the last fragment of Shane’s utopia) at one end of the aqueduct—even that has evidence of human debris. The postmodern industrial gallery installations that are the subject of bourgeois ruminations have indeed merged with the world they inadequately represent.

Refn tends to shoot in fairly close, capturing small vignettes of the city rather than cityscapes. Here the sources are as much photographers like William Eggleston and Stephen Shore as painters, the effect being to show instances of decay, such as unwholesome restaurants (the pizzeria with its strange red-and-white glass door that replicates its tablecloths), garages, diners, an image of a pawnshop on an antiquated TV set. When the Kid takes Irene and Benicio on a little excursion, one of the very few light moments, he drives them down the concrete surface of the Los Angeles River, a much-used movie location. This “river,” with its absolute human artifice—it is mostly a human construction—has only a stream of (filthy?) water in its center. The trio disembarks at a swatch of nature (the last fragment of Shane’s utopia) at one end of the aqueduct—even that has evidence of human debris. The postmodern industrial gallery installations that are the subject of bourgeois ruminations have indeed merged with the world they inadequately represent.Human interactions are abstracted and reduced to graphic art, such as the final death struggle between the Kid and Bernie. We see its shadow rather than the event itself, as the camera aims at the surface of the parking lot, bathed in magic-hour light, the two men’s elongated, writhing shadows recalling Giacometti or the work of Robert Longo. In the film’s final stylistic flourish, the Kid sits in his car after the death of Bernie. The camera starts at his bloody sneaker and moves upward until we see his face. He holds his stomach, which one assumes has been badly wounded by Bernie’s sudden knife attack. The Kid’s face is seen in profile, his eyes unblinking during the prolonged take, conveying that he is dying or dead. But he blinks and reaches for his car key, starts the engine, and drives away into the polluted LA streets. This attempt to mythologize the Kid corresponds with the ending of Shane, where the wounded hero, slumped in his saddle, rides up the mountain into heaven. Whether Shane lives or dies is immaterial, since a kind of sainthood has been conferred upon him. The similar gesture at the end of Drive has nothing like this resonance. The Kid seems “undead,” his resurrection unjustified, since his function in relieving this decaying society has been less than salvific. Meanwhile, Irene, now alone to raise Benicio and in the near-poverty of her subsistence-level waitress job, knocks at the door of the Kid’s empty apartment. There is no response, so she walks away.

Sound

The film’s sound design, and the score by Cliff Martinez, helps convey a familiar theme of the postmodern cinema. Drive is about a “fallen world,” one beyond remedy, but outside of any and all alternative visions of human interaction. It is a world too far gone to partake even of the Christian/metaphysical suggestions of Se7en. The soundtrack is always alive, containing a low, threatening rumble, or a variety of ambient/techno/industrial pulsations and drones, some with a rather melancholy aspect. To continue the Shane analogy, the music of Drive could be reasonably termed the total antithesis of Victor Young’s romantic score, with its main theme so robust and full of a kind of wistful optimism (”The Call of the Faraway Hills”), the sound and image of the film’s opening conjoined to announce the righteous arrival of the male, the future full of possibility, the hero enjoying an empathetic relationship with the lush, verdant landscape (quickly associated with female sexuality).

Several pop songs are included on the soundtrack, always problematical. Michael Mann was unjustly accused of bringing the “rock video aesthetic” to cinema; the initial dismissal of Mann was unfair, since he proved himself sensitive to the sound/image relationship, and was in no way involved in “selling” popular music. Rock songs can be used very arbitrarily, and often in a way that undermines the radical impulses of the best forms of rock music. Among the more ludicrous examples that come to mind is a shot in the Steven Seagal film Under Siege. We see a battleship that has just been taken over by terrorists. Suddenly Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile” appears on the soundtrack. The only purpose (if there is any conscious one) of making such use of work by a radical (in every sense) artist is to use rock’s “badass” quality, forgetting entirely its content or historical moment. The most difficult aspect of rock songs, even more so than many musical scores, is their tendency to tell you exactly how to feel, assumed to be necessary, it appears, for an increasingly dumbed-down public.

Refn, like Mann, takes an eclectic approach to music, “sampling” of “found tunes,” incorporating songs into Martinez’s score to add a sense of counterpoint to the image. The College/Electric Youth song “A Real Hero,” appears twice in the film, notably when Kid takes Irene and Benicio for the drive in the LA River. We don’t know enough as yet to sense that the Kid is by no means a hero, but the song itself, as literal as it is, gives us clues. The refrain “a real hero, a real human being” is itself instructive, as if one must be a hero (whatever that is) in order to be a human being. It seems to me that the word “hero” is one of the most overused expressions in popular discourse. Newscasters use it when someone stops to assist a stranded motorist. Ordinary acts of basic human compassion are “heroic” in a totally atomized, alienated society. The idea of the hero, about which there was much nervous cultural commotion in the 80s, is scrutinized here to suggest that the charismatic male, long seen by bourgeois society as a measure of that society’s well being, has now become a signifier of that society’s coming apart. The song “Under Your Spell” seems more problematical. We hear its lyrics “I can’t eat, I can’t sleep,” conveying a kind of teenage sexual preoccupation, as Kid sits alone with his carburetor while Irene hosts a party for her husband Standard, just released from prison. The Kid steps out of his own apartment, spotting Irene sitting alone in the hall. It turns out that the loud music is diegetic, coming from the party, for which Irene apologizes. When the Kid leaves his apartment, he takes the carburetor with him—where is he going? Just after he sees Irene, Standard steps out of their apartment to meet the Kid for the first time. “Under Your Spell” could be read as much about the Kid’s privacy, his Zen-like focus on his tools and anti-social disposition being disrupted, as about his sexual interest in Irene.

Refn, like Mann, takes an eclectic approach to music, “sampling” of “found tunes,” incorporating songs into Martinez’s score to add a sense of counterpoint to the image. The College/Electric Youth song “A Real Hero,” appears twice in the film, notably when Kid takes Irene and Benicio for the drive in the LA River. We don’t know enough as yet to sense that the Kid is by no means a hero, but the song itself, as literal as it is, gives us clues. The refrain “a real hero, a real human being” is itself instructive, as if one must be a hero (whatever that is) in order to be a human being. It seems to me that the word “hero” is one of the most overused expressions in popular discourse. Newscasters use it when someone stops to assist a stranded motorist. Ordinary acts of basic human compassion are “heroic” in a totally atomized, alienated society. The idea of the hero, about which there was much nervous cultural commotion in the 80s, is scrutinized here to suggest that the charismatic male, long seen by bourgeois society as a measure of that society’s well being, has now become a signifier of that society’s coming apart. The song “Under Your Spell” seems more problematical. We hear its lyrics “I can’t eat, I can’t sleep,” conveying a kind of teenage sexual preoccupation, as Kid sits alone with his carburetor while Irene hosts a party for her husband Standard, just released from prison. The Kid steps out of his own apartment, spotting Irene sitting alone in the hall. It turns out that the loud music is diegetic, coming from the party, for which Irene apologizes. When the Kid leaves his apartment, he takes the carburetor with him—where is he going? Just after he sees Irene, Standard steps out of their apartment to meet the Kid for the first time. “Under Your Spell” could be read as much about the Kid’s privacy, his Zen-like focus on his tools and anti-social disposition being disrupted, as about his sexual interest in Irene.Riz Ortolani’s 1971 composition “Oh My Love,” written for the film Goodbye Uncle Tom and performed by Katyna Ranieri, may be the most eccentric sampling of all. It is one of those strained, obtusely philosophical sung versions of a main film theme written in the 60s and 70s by Ortolani and Ennio Morricone for the pop charts of Europe. In Goodbye Uncle Tom, “Oh My Love” seems merely mawkish. In Drive, its sophomoric transcendentalism helps form the film’s final “aria,” a grotesque counterpoint, as accounts are settled. The singer tells us about the “rising sun embracing nature,” but “not for men who live in shadows,” as the Kid approaches Nino’s Pizzeria in his bizarre mask. The moment is hyperbolic, and perhaps a misstep, but it is worth observing that the line “oh my love” first appears on the soundtrack as the Kid touches the dead Shannon, another male pieta. “Oh My Love,” is middle-brow entertainment of the early 70s, but it embraces, however awkwardly, the leftist and counterculture sentiments of its period, if only for a sort of co-optation. In this murderous and overwhelmingly dark moment of Drive, one must consider the extent to which those sentiments have been suffocated.

Against Drive

As I finished this essay, I watched several interviews with Nicholas Winding Refn on YouTube. His comments confirm some of the thoughts I offer here, but challenge others. He strikes me as an intelligent young man, whose career may just be getting underway— or coming to a conclusion as he embraces the current Hollywood. His age is a troubling factor. He seems to have a wide-ranging knowledge of film (see Lenny’s amusing rattling-off of directors’ names in Bleeder), but he is far too impressed with films like First Blood, Escape from New York, and other overrated 80s films, as Hollywood slid into its intellectual bankruptcy, far worse now than then. He is not Tarantino, and I sincerely hope that we see no manifestation of that sensibility in his future work, but his age might make him a “movie brat” in the worst sense (I can’t tell his knowledge of the other arts).

My biggest concern, as I re-screen his work, is that Drive may indeed represent a step backward as Hollywood culture notices him—he seems to want to work simply to keep working, a noble enough idea, but this ethic today puts the artist in an imperiled position. Would one want to make anything to keep working, to put up with any demands? (Such is the case with people like Christopher Nolan.) That’s certainly how one exists under capital, but for Refn, and any filmmaker, the issue isn’t one of survival as it is for someone mopping a floor, or working within social service programs during the age of privatization. Looking at the Pusher films, Bleeder, and even Valhalla Rising, all of which make strong statements about masculinity and the disintegration of the capitalist state, I wonder if Drive adds anything not already said by Michael Mann. Some reviews have attacked the film for bizarre reasons, some saying it repeats Mann, many mentioning it as a “remake” of Walter Hill’s The Driver (1972)—in what way does Drive have anything in common with this film, where a stoic getaway driver (a poorly cast Ryan O’Neal) plays a cat-and-mouse game with a cop (Bruce Dern)?

My biggest concern, as I re-screen his work, is that Drive may indeed represent a step backward as Hollywood culture notices him—he seems to want to work simply to keep working, a noble enough idea, but this ethic today puts the artist in an imperiled position. Would one want to make anything to keep working, to put up with any demands? (Such is the case with people like Christopher Nolan.) That’s certainly how one exists under capital, but for Refn, and any filmmaker, the issue isn’t one of survival as it is for someone mopping a floor, or working within social service programs during the age of privatization. Looking at the Pusher films, Bleeder, and even Valhalla Rising, all of which make strong statements about masculinity and the disintegration of the capitalist state, I wonder if Drive adds anything not already said by Michael Mann. Some reviews have attacked the film for bizarre reasons, some saying it repeats Mann, many mentioning it as a “remake” of Walter Hill’s The Driver (1972)—in what way does Drive have anything in common with this film, where a stoic getaway driver (a poorly cast Ryan O’Neal) plays a cat-and-mouse game with a cop (Bruce Dern)?To my mind, at this writing, the Kid is a more damaged and destructive figure than those conceived so far by Mann and other mature filmmakers of this era; he is simultaneously enervated and explosive, lacking in judgment and possessed by mania, and as such is a rendering of the further disintegration of the patriarchal capitalist order of things. We can reconsider all of this as Refn’s career unfolds.

My apologies for lifting the title of Mario Praz’s masterful The Hero in Eclipse in Victorian Fiction

Christopher Sharrett is Professor of Communication and Film Studies at Seton Hall University, USA. He has written for Film International and other publications. He is currently listening to Bach cantatas under the direction of John Eliot Gardiner, and a range of industrial noise from Merzbow to Brighter Death Now, which he feels the most authentic representation of the viciousness of the disintegrating late capitalist state.

LINK

Comments

Post a Comment